Business

The World Bank Group unveiled a new system on Thursday to rank countries based on their success in developing human capital, an effort to prod governments to invest more effectively in education and healthcare.

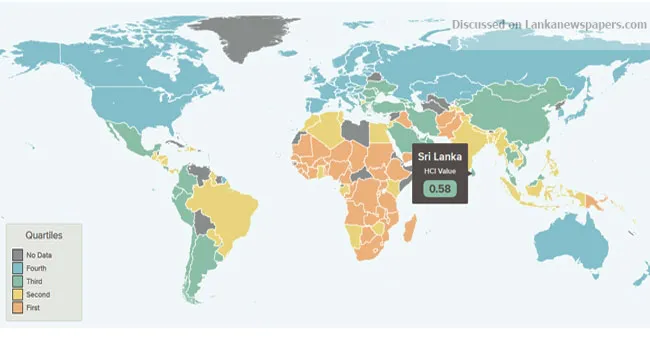

The bank’s “Human Capital Index,” showed poor African countries fared the worst in the rankings, with Chad and South Sudan taking the two lowest spots, while Singapore topped the list, followed by South Korea, Japan and Hong Kong.

Sri Lanka with an overall HCI value of 0.58 ranks ahead of its South Asian neighbors India, Pakistan and Bangladesh.

The rankings, based on health, education and survivability measures, assess the future productivity and earnings potential for citizens of 157 of the World Bank’s member nations, and ultimately those countries’ potential economic growth.

According to the Human Capital Index, a child born in Sri Lanka today will be 58 percent as productive when she grows up as she could be if she enjoyed complete education and full health. That compares with 44 percent in India and 39 percent in Pakistan. Bangladesh boasts 48 percent and Nepal 49 percent in the same category.

In the probability of survival, Sri Lanka surpasses its neighbours with 99 out of 100 children surviving to age 5, whereas it is 97 in Bangladesh, 96 in India and 93 in Pakistan.

In Sri Lanka, a child who starts school at age 4 can expect to complete 13 years of school by her 18th birthday. In Bangladesh, a child who starts school at age 4 can expect to complete 11 years of school by her 18th birthday. In India, a child can expect to complete 10.2 years of school in the same category, while it is just 8.8 years in Pakistan.

In harmonised test scores, students in Sri Lanka score 400 - the highest in the region - on a scale where 625 represents advanced attainment and 300 represents minimum attainment. It is 369 in Nepal, 368 in Bangladesh and 355 in India, followed by Pakistan at 339.

In learning-adjusted Years of School, factoring in what children actually learn, expected years of school is only 8.3 years in Sri Lanka. That compares with 6.5 years in Bangladesh, 5.8 years in India and 4.8 years in Pakistan.

Across Sri Lanka, 87 percent of 15-year olds will survive until age 60. This statistic is a proxy for the range of fatal and non-fatal health outcomes that a child born today would experience as an adult under current conditions.

Bangladesh in on par with Sri Lanka in this indicator while across India, 83 percent of 15-year olds will survive until age 60. Compared to India, it is slightly higher in Pakistan -- 84 percent. The rate is 85 percent in Nepal.

In terms of healthy growth (not stunted rate), 83 out of 100 children are not stunted in Sri Lanka 64 out of 100 children are not stunted in Bangladesh. And 17 out of 100 children are stunted, and so at risk of cognitive and physical limitations that can last a lifetime.

The report states that between 2012 and 2017, the HCI value for Sri Lanka remained approximately the same at 0.58. In 2017, Sri Lanka’s HCI is higher than the average for its region and income group.

The Human Capital Project seeks to raise awareness and increase demand for interventions to build human capital. It aims to accelerate better and more investments in people. The Project has three elements (i) the Human Capital Index, (ii) a program to strengthen research and measurement on human capital; and (iii) support to countries to accelerate progress in raising human capital outcomes.

The index was unveiled at the World Bank and International Monetary Fund annual meetings on the Indonesian island of Bali.

The index measures the mortality rate for children under five, early childhood stunting rates due to malnutrition and other factors, and health outcomes based on the proportion of 15-year-olds who survive until age 60.

It measures a country’s educational achievement based on the years of schooling a child can expect to obtain by age 18, combined with a country’s relative performance on international student achievement tests.

Countries in Africa with high childhood stunting rates and low access to formal education fared worst, while wealthier nations with strong educational systems fared best.

In Chad, the lowest country ranked on the list, the World Bank said productivity and earnings potential would be only about 29 percent of what their potential would be under ideal conditions there.

In top-ranked Singapore, the earnings potential was 88 percent of potential, while in the United States, ranked 24th between Israel and Macau, productivity and earnings were measured at 76 percent of potential.

The index, irrespective of whether it is high or low, is not an indication of a country’s current policies or initiatives, but rather reflects where it has emerged over years and decades.

Put simply, the index measures what the productivity of a generation is, compared to what it could be, if they had benefitted from complete education and good health.

The index ranges from 0 to 1 and takes the highest value of 1 only if a child born today can expect to achieve full health (defined as no stunting and survival up to at least age 60) and complete her education potential (defined as 14 years of high-quality school by age 18).

The HCI measures the amount of human capital that a child born today can expect to attain by age 18. It conveys the productivity of the next generation of workers compared to a benchmark of complete education and full health. It is constructed for 157 countries.

It is made up of five indicators: the probability of survival to age five, a child’s expected years of schooling, harmonized test scores as a measure of quality of learning, adult survival rate (fraction of 15-year olds that will survive to age 60), and the proportion of children who are not stunted.

Globally, 56 percent of all children born today will grow up to be, at best, half as productive as they could be; and 92 percent will grow up to be, at best, 75 percent as productive as they could be.

Popular News

Two including 2-yr-old killed in fatal accident at Dehiattakandiya

2025-12-17

General

Missing yellow anaconda hatchling found at Dehiwala Zoo

2025-12-17

General

FM accepts US$ 2.5 million grant assistance from Japan

2025-12-17

Politics