Uncategorized

‘ONUR never dictated terms’

When a film is funded by an organization headed by a leading political figure it is difficult to believe that it does not promote that individual’s political agenda. But Asoka Handagama, Vimukthi Jayasundara and Prasanna Vithanage, the directors of the omnibus film Thundenek, under the English title ‘Her. Him. The Other’ maintain that the film does not adavance a personal political agenda and is a genuine effort to promote reconciliation. The film produced by Office of Unity and Reconciliation Sri Lanka premiered on February 27. It will be screened in cinemas starting mid March. Thundenek is of a genre Sri Lankan audiences are not frequently exposed to; anthology or omnibus film. The Island caught up with the reputed directors to discuss how the unusual combination and the sensitive themes will sit with Sri Lankan moviegoers. Thundenek three short films in one. ‘Her’ directed by Prasanna Vithanage, based on a true story is about a pro-LTTE videographer, Kesa, who travels from the North in search of ‘Her’, the woman in the photograph which Kesa finds in a wallet of a soldier from the South. It’s a story about coming to terms with his own conscience. Vimukthi Jayasundara’s ‘Him’ is about a Sinhala teacher, who, while professing Buddhism tries to deceive his own conscience by refusing to believe the re-birth of a Tamil militant into a Sinhala family. It is a film about identity. ‘The Other’ by Asoka Handagama is about a Tamil mother who comes to Colombo in search of his missing son, an LTTE cadre. She finds a Sinhala solder whom she considers her lost son. Again a film about identity issues. "For many years had been planning to do a film not on the war, but the impact of the war," said Handagama. Although they had no inkling of the story they knew it would be about the dual perspectives, both Sinhala and Tamil, of the impact of the war. Having heard Kesa’s story, the trio now had a storyline. Despite making the Tamil film Ini Avan on post war Jaffna, Handagama felt the absence of a genuine effort at reconciliation. Handagama opined that, had Sri Lanka not been able to fully achieve reconciliation. Jayasundara pointed out that the political atmosphere was not conducive to such works of post war analysis. "In fact, the country is still reluctant to access what happened during the war. The war has many long enduring effects on all races," pointed out Jayasundara. Concurring with Jayasundara, Handagama admitted that there were still unresolved issues. "We wanted to make a movie that would prompt a dialogue on such issues," said Handagama. "Our film is about the aftermath of the war," said Vithanage. "The war created many stories - stories without closure. All three stories in Thundenek are about people who are looking for closure." He pointed out that the Sri Lankan people could easily relate the polarization of communities, thus the title ‘Her. Him. The Other’. "For the Sinhala people Tamils have become The Other and vice versa; the same goes for Muslims." "War was just the effect, not the cause," said Jayasundara. "It’s just simmering beneath the surface and can resurface any moment. Using violence against violence doesn’t provide a lasting solution."-DMP33.jpg) The film is an anthology or omnibus film. The first one made in the history of Sri Lankan cinema was the 1970 film ‘Thewatha’ by Titus Thotawatte. When asked how this genre, a fairly novel concept, would be received by the public, Handagama said that it would no doubt be a unique experience for Sri Lankan audiences. "We are three different directors, who use different filmmaking styles to look at the same problem in three different ways. It’s one ticket to meet three directors."

In fact, Handagama himself has previously admitted that he is an extension of Dharmasena Pathiraja, Vithanage an extension of Lester James Peries and Jayasundara a combination of both Handagama and Vithanage. When asked how they had maintained their identities while making a film together, Handagama admitted that some compromises had to be made. "But we maintained our identities within those limits. For example, Vimukthi likes to pace his scenes slow. Prasanna’s and mine are relatively fast paced."

Handagama said that,therefore,Jayasundara’s film was placed in the middle. "So it blends well with the different rhythms. It sets a different kind of tempo for the whole film." As most omnibus films ‘Thundenek’ is three films linked together thematically. "Although Jayasundara’s film seemingly does not connect with the other two stories, by placing it in the middle we were able to connect the whole film thematically," explained Handagama. And the thread that interconnects them is ‘identity’.

"The three short films raise issues on the same topic to build a discourse on reconciliation," said Handagama. Vithanage pointed out that introspection was another recurrent theme in the film. "All three characters in the separate short films are looking for someone else, In ‘The Other’, they end up finding themselves in the other," said Vithanage.

When asked how, they thought, the film would be received by Sinhala and Tamil communities, considering the sensitive themes the film deals and criticism levelled at the all three directors for their previous war-related works, Handagama said that the film targeted mainly the Sinhala people.

"The oppressed in South Africa were the black. But after Nelson Mandela became the President of South Africa, in the post Apartheid period, the oppressed came to power. It was they who extended the hand of reconciliation," said Handagama. He pointed out that a strong understanding of a conflict was necessary for reconciliation efforts to reach to fruition. "The South African government appointed a Truth and Reconciliation Commission to work towards reconciliation. Only after such efforts were they able to achieve reconciliation and become what’s known today as the Rainbow Nation."

Handagama said, "The Tamil people have to come to terms with the reality that they cannot have a separate state, but this will happen only if there is a genuine effort on our part towards reconciliation. As I said before the offer of reconciliation should be made by those in power, the Sinhala people. The Sinhala people have to accept the reality that they have to make certain compromises to achieve reconciliation. I think the film can prompt people to look at the issues raised, differently,"

Vithanage opined that no matter the audience, if the emotions conveyed were truthful, it would be well received.

Handagama opined that releasing the film commercially would’nt serve their purpose. "The film has to reach grassroots level." He said that the premier had received positive feed back with requests from both Sinhala and Tamil communities.Some people had offered to organize public screenings. Vithanage said that they also intended to take the film on to the digital platform. "Our motto in making the film accessible for the public is ‘anywhere any time’," said Vithanage.

The directors also hope to screen the film in the Locarno, Moscow and Hong Kong film festivals.

When asked why they had used an all-new cast, Handagama said that veteran actors would have been less convincing. New actors would allow audiences to identify themselves with those characters easily. "I play the role of myself in Prasanna’s movie. And Kesa, the videographer, plays his own part. It’s not actually acting." All the Tamil speaking actors for Vithanage’s film were from Jaffna. His team conducted a two-day workshop for 25 aspiring film-makers. "Their input can enhance not only Sinhala cinema, but the Sri Lankan cinema."

The film was funded by the Office of Unity and Reconciliation (ONUR) Chaired by Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga and thereafter it may be claimed that ‘Thundenek’ promotes a political agenda, Handagama said that they were willing to cater to anyone who wanted to promote reconciliation. "Provided we are given freedom to do it our way," . "We were approached by ONUR to make a film on reconciliation. We put forth our idea. This film is not a rosy story about reconciliation. Our intentions were to provoke a discourse," said Handagama, adding that ONUR had never interfered with their work.

Asked whether reconciliation could be achieved through art forms such as film and plays, Handagama answered in the negative. "But Art can provoke a discourse on reconciliation and persuade people to achieve it by making them accept the reality. The actual reconciliation should be addressed through a political process."

Jayasundara and Vithanage opined that war dehumanises people and art’s purpose is to re-humanise them. "I don’t make films on subjects like reconciliation," said Vithanage. "I make films on people like Kesa." He explained that when a film was funded the funding party expects film-makers to come up with solutions for the issue. "An artiste’s role is not to provide solutions on a platter, but to raise the questions, for example whether reconciliation is really happening."

The film is an anthology or omnibus film. The first one made in the history of Sri Lankan cinema was the 1970 film ‘Thewatha’ by Titus Thotawatte. When asked how this genre, a fairly novel concept, would be received by the public, Handagama said that it would no doubt be a unique experience for Sri Lankan audiences. "We are three different directors, who use different filmmaking styles to look at the same problem in three different ways. It’s one ticket to meet three directors."

In fact, Handagama himself has previously admitted that he is an extension of Dharmasena Pathiraja, Vithanage an extension of Lester James Peries and Jayasundara a combination of both Handagama and Vithanage. When asked how they had maintained their identities while making a film together, Handagama admitted that some compromises had to be made. "But we maintained our identities within those limits. For example, Vimukthi likes to pace his scenes slow. Prasanna’s and mine are relatively fast paced."

Handagama said that,therefore,Jayasundara’s film was placed in the middle. "So it blends well with the different rhythms. It sets a different kind of tempo for the whole film." As most omnibus films ‘Thundenek’ is three films linked together thematically. "Although Jayasundara’s film seemingly does not connect with the other two stories, by placing it in the middle we were able to connect the whole film thematically," explained Handagama. And the thread that interconnects them is ‘identity’.

"The three short films raise issues on the same topic to build a discourse on reconciliation," said Handagama. Vithanage pointed out that introspection was another recurrent theme in the film. "All three characters in the separate short films are looking for someone else, In ‘The Other’, they end up finding themselves in the other," said Vithanage.

When asked how, they thought, the film would be received by Sinhala and Tamil communities, considering the sensitive themes the film deals and criticism levelled at the all three directors for their previous war-related works, Handagama said that the film targeted mainly the Sinhala people.

"The oppressed in South Africa were the black. But after Nelson Mandela became the President of South Africa, in the post Apartheid period, the oppressed came to power. It was they who extended the hand of reconciliation," said Handagama. He pointed out that a strong understanding of a conflict was necessary for reconciliation efforts to reach to fruition. "The South African government appointed a Truth and Reconciliation Commission to work towards reconciliation. Only after such efforts were they able to achieve reconciliation and become what’s known today as the Rainbow Nation."

Handagama said, "The Tamil people have to come to terms with the reality that they cannot have a separate state, but this will happen only if there is a genuine effort on our part towards reconciliation. As I said before the offer of reconciliation should be made by those in power, the Sinhala people. The Sinhala people have to accept the reality that they have to make certain compromises to achieve reconciliation. I think the film can prompt people to look at the issues raised, differently,"

Vithanage opined that no matter the audience, if the emotions conveyed were truthful, it would be well received.

Handagama opined that releasing the film commercially would’nt serve their purpose. "The film has to reach grassroots level." He said that the premier had received positive feed back with requests from both Sinhala and Tamil communities.Some people had offered to organize public screenings. Vithanage said that they also intended to take the film on to the digital platform. "Our motto in making the film accessible for the public is ‘anywhere any time’," said Vithanage.

The directors also hope to screen the film in the Locarno, Moscow and Hong Kong film festivals.

When asked why they had used an all-new cast, Handagama said that veteran actors would have been less convincing. New actors would allow audiences to identify themselves with those characters easily. "I play the role of myself in Prasanna’s movie. And Kesa, the videographer, plays his own part. It’s not actually acting." All the Tamil speaking actors for Vithanage’s film were from Jaffna. His team conducted a two-day workshop for 25 aspiring film-makers. "Their input can enhance not only Sinhala cinema, but the Sri Lankan cinema."

The film was funded by the Office of Unity and Reconciliation (ONUR) Chaired by Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga and thereafter it may be claimed that ‘Thundenek’ promotes a political agenda, Handagama said that they were willing to cater to anyone who wanted to promote reconciliation. "Provided we are given freedom to do it our way," . "We were approached by ONUR to make a film on reconciliation. We put forth our idea. This film is not a rosy story about reconciliation. Our intentions were to provoke a discourse," said Handagama, adding that ONUR had never interfered with their work.

Asked whether reconciliation could be achieved through art forms such as film and plays, Handagama answered in the negative. "But Art can provoke a discourse on reconciliation and persuade people to achieve it by making them accept the reality. The actual reconciliation should be addressed through a political process."

Jayasundara and Vithanage opined that war dehumanises people and art’s purpose is to re-humanise them. "I don’t make films on subjects like reconciliation," said Vithanage. "I make films on people like Kesa." He explained that when a film was funded the funding party expects film-makers to come up with solutions for the issue. "An artiste’s role is not to provide solutions on a platter, but to raise the questions, for example whether reconciliation is really happening."

Share:

Popular News

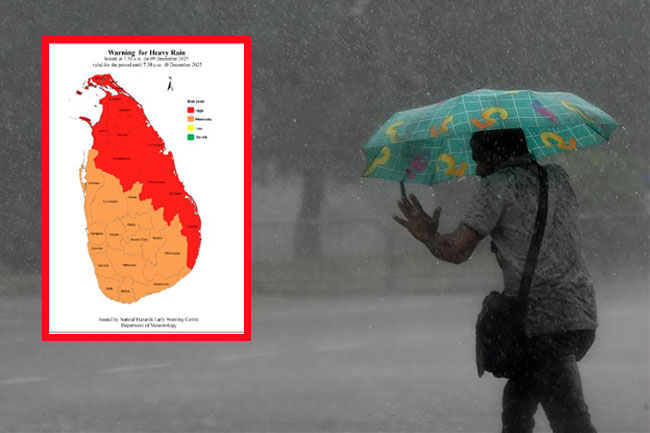

Advisory issued for heavy rainfall above 100 mm

2025-12-09

General

Trump warns of new tariffs on India, says they should not “Dump Rice” in US

2025-12-09

Business

Youth murdered with sharp weapon over financial dispute in Panadura

2025-12-09

General

Former Chairman of SLBFE Mohammed Hilmi granted bail

2025-12-09

General

One-fifth of Sri Lanka inundated by cyclone Ditwah - UNDP analysis

2025-12-09

Politics